Many prominent people in the theatre industry have wondered if the process of designing and building theatres could be improved by learning from the theatre production process and the people engaged in it. This dissertation considers this idea. It compares the architectural process, outlined by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Plan of Work 2013, with the production process used in the majority of producing theatre companies in Britain.

This dissertation begins by discussing the difficulties involved in constructing a building for the arts, and then it goes on to contextualise this debate in the existing literature. The methodology is discussed, followed by the presentation of research that has been undertaken by the author. It compares the two processes and discusses the possibility of theatre-makers being included in the building design process. It ends with an in-depth look at The Squire Performing Arts Centre, a recently built theatre case study. Conclusions are drawn from the research to make a judgement on if the production process can inform the construction industry.

This dissertation begins by discussing the difficulties involved in constructing a building for the arts, and then it goes on to contextualise this debate in the existing literature. The methodology is discussed, followed by the presentation of research that has been undertaken by the author. It compares the two processes and discusses the possibility of theatre-makers being included in the building design process. It ends with an in-depth look at The Squire Performing Arts Centre, a recently built theatre case study. Conclusions are drawn from the research to make a judgement on if the production process can inform the construction industry.

Introduction

In the last few decades, more arts buildings have been built in Britain than ever, making this dissertation research into theatre architecture important for both theatre and architecture. This resurgence brought many accounts of tensions and over-compromising new designs, resulting in inefficient building processes and poor building outcomes. Some theorists and architects suggest that designs could be more effective if architects learnt more about how theatres are used by listening more to theatre-makers throughout the design process, suggesting that architecture needs to be more about theatre.

Theatres must suggest a shrine but house a factory. They are one of the most complex types of building to design, and they have to be bespoke, designed differently by architects due to their complexity. Unlike most buildings, simple architectural specifications are not enough to satisfy the needs of building users, they also need ethereal elements that should be theatrically conceived, not architecturally conceived. This makes the idea of including theatre professionals in the design process much more logical.

Theatres must suggest a shrine but house a factory. They are one of the most complex types of building to design, and they have to be bespoke, designed differently by architects due to their complexity. Unlike most buildings, simple architectural specifications are not enough to satisfy the needs of building users, they also need ethereal elements that should be theatrically conceived, not architecturally conceived. This makes the idea of including theatre professionals in the design process much more logical.

This dissertation discusses theatre architecture and examines the construction process for arts buildings. Ultimately it aims to answer the research question:

Can ideas from the theatre industry or the production process inform and alleviate issues experienced by architects when working with theatre projects?

Literature and Methodology

Investigating buildings for the arts has only been investigated in depth over the last few decades, so there was a limited amount of literature about linking the production process in theatres to the building of theatres. However, it fits into several wider discussions and theorists’ ideas examined for this dissertation; these fit into the categories of theatre architecture in general, the production process in theatre and the construction process. A range of literature was consulted, and a gap was found where these topics intersect.

Three different research methods were used: literary research, conducting semi-structured interviews and contextualising the theory within a case study. Cross-examining the data from each source identified resounding themes and allowed conclusions to be drawn with little more certainty. The reality of both the construction and production industry is that each project is different so it is only feasible to study individual cases, and any conclusions cannot always be applied to every case.

Three different research methods were used: literary research, conducting semi-structured interviews and contextualising the theory within a case study. Cross-examining the data from each source identified resounding themes and allowed conclusions to be drawn with little more certainty. The reality of both the construction and production industry is that each project is different so it is only feasible to study individual cases, and any conclusions cannot always be applied to every case.

The Production Process

The production process in theatre has many similarities to projects in the construction industry. In particular, the set designer is analogous to the architect in many ways. Their role in theatre involves designing a space for their show to sit in, and the stages of this are similar to the RIBA Stages of work followed by an architect. An initial design concept is conceived from the script's needs and the director's ideas; after several meetings, technical drawings and a scale model are made to present the scheme, and eventually, the set is built for the performance. The reality of theatre is that the production team work together towards a common goal in a dynamic and evolutionary design process, often leading to a strong camaraderie within the team.

The Construction Process

The RIBA Plan of work outlines the definite model for the design and construction process for architects; it is used for all theatre building projects and so was important to consider. It is highly structured and organises the process of briefing, designing, constructing, maintaining, operating and using a building into eight key stages, which encourages efficiency and coordination across the construction industry. Although this has been designed to be flexible depending on building type, accounts of building for the arts suggest that the linear nature of the Plan of Work in unsuitable for theatres. Due to their complexity the restrictions of rigid work stages can stifle productivity and create adversity in the design team when consultants are brought in too late or a budget has been fixed. Cooperation within the design team is often adversarial as they each have different priorities within the design, which contrasts the camaraderie found in the theatre.

The Set Designer and the Architect

The most relatable profession in theatre to the architect is the set designer; during many building projects they are seen as the middleman between the director and the architect because they have the design knowledge to communicate with the architect and the theatre knowledge of the director. While theory suggests that scenic design and architecture are similar there are fundamental differences between the two disciplines, and it is debatable whether their knowledge can be useful in an architectural project. Set designers thrive on limitations such as a fixed deadline and ideas posed by the script and director, whereas architects are quite the opposite. Architecture has to be much more permanent so the design must be enduring and neutral, whereas in theatre all design elements must point towards a single narrative.

Set designers have rarely taken a positive, active role in theatre architecture, but from interviews with theatre professionals it is clear that theatre makers are keen to be involved with the process. Each production team member interviewed clearly respected the work of the architect and did not claim to be able to design a theatre, instead they would want to be consulted on the functionality of the space. Examples of this collaboration, such as in the Tara Arts Centre, make it clear that this is effective. When interviewing an architect of theatre projects there was a clear mistrust between the disciplines and she explained that because theatres are so complex and technical to design it was difficult for to see how theatre personnel could be added to the architectural design team.

Set designers have rarely taken a positive, active role in theatre architecture, but from interviews with theatre professionals it is clear that theatre makers are keen to be involved with the process. Each production team member interviewed clearly respected the work of the architect and did not claim to be able to design a theatre, instead they would want to be consulted on the functionality of the space. Examples of this collaboration, such as in the Tara Arts Centre, make it clear that this is effective. When interviewing an architect of theatre projects there was a clear mistrust between the disciplines and she explained that because theatres are so complex and technical to design it was difficult for to see how theatre personnel could be added to the architectural design team.

“Art is more ephemeral, whereas architecture is permanent. Theatre is about convincing an audience of an illusion and working to strict deadlines, architecture involves real people confronting real space and operate a much more pliable calendar.”

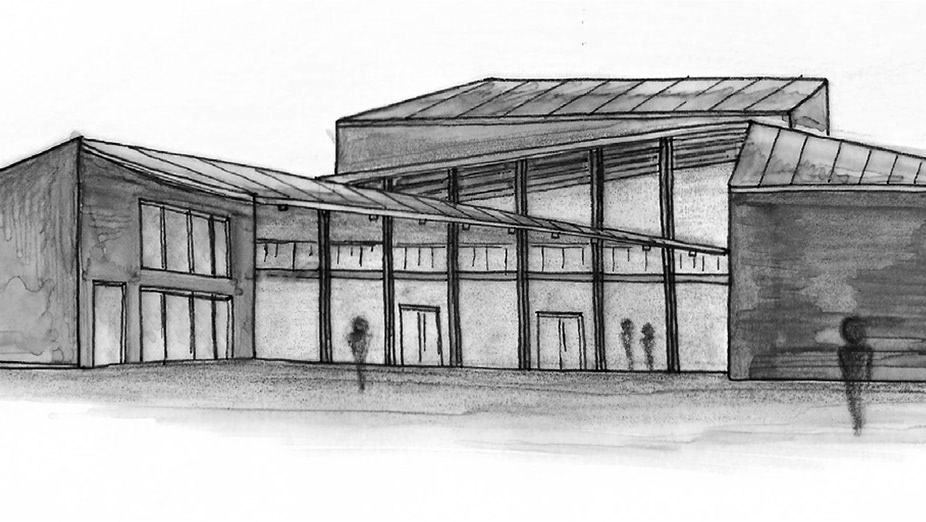

Squire Performing Arts Centre Section | Marsh Grochowski Architects

The Squire Performing Arts Centre

The case study research recounts how a school theatre located in Nottingham was designed and constructed, having gained information from the project’s official documents and interviews with Suzy Hunt, the architect, and Jeremy Dunn, the clients representative. Comments are also made on the building’s success as it has now been in use for several years; this information was gained from interviews with Sally Timpson, the events coordinator of the theatre, and Anita Bush, its manager.

Interviewing both Hunt and Dunn, it was clear that the collaboration between the client and architect made this project successful. Despite large issues during the planning process and setbacks during construction, the client fought hard for the project, and they were passionate about having a theatre. This project didn’t use theatre professionals, but the clear views of the client acted similarly in this case; if they had been used, they have been able to mitigate the frustrations of the current production team, such as a lack of storage in the building.

Interviewing both Hunt and Dunn, it was clear that the collaboration between the client and architect made this project successful. Despite large issues during the planning process and setbacks during construction, the client fought hard for the project, and they were passionate about having a theatre. This project didn’t use theatre professionals, but the clear views of the client acted similarly in this case; if they had been used, they have been able to mitigate the frustrations of the current production team, such as a lack of storage in the building.

SPACE Ground Floor Plan | Marsh Grochowski Architects

Discussions and Conclusions

Both the production and construction processes go through several similar stages of linear instructions so that they are completed efficiently, but in practice they are approached very differently. The strict deadlines involved in the theatre teamed with a quick timetable instigates a level of production and camaraderie within the design team which is unmatched in architecture. Instead architects have to spend much of their time compromising ideas into a design rather than working beside their peers towards a common goal.

The issues faced by designers when developing a building from the arts stem from the complexity of the building type, and the architect’s lack of knowledge of them. Seen as the bespoke and complex nature of theatres will not change, the onus is on the architect to improve their knowledge of theatre buildings in order to improve the building process and its outcome.

The issues faced by designers when developing a building from the arts stem from the complexity of the building type, and the architect’s lack of knowledge of them. Seen as the bespoke and complex nature of theatres will not change, the onus is on the architect to improve their knowledge of theatre buildings in order to improve the building process and its outcome.

From interviews, theatre makers are passionate about being involved in theatre architecture with their priorities largely focussing on the functionality of the space. Involving theatre professionals would not result in major design changes, but small functional input, particularly during value engineering, could help to mitigate the frustrations of the users of the space.

Effective communication within the design team and between the client and architect is vital for the success of building for the arts. One of the most critical aspects of improving the process of theatre design is to not only incorporate theatre professionals, but to also adopt their less adversarial approach to designing and collaborating. Replicating this camaraderie with ambition and drive will certainly benefit the efficiency of building projects and result in better building outcomes. This could be made feasible by involving consultants earlier in the design process than is suggested in the RIBA Plan of Work, allowing each member of the design team to have the same opportunity to contribute to the design, work with the client and collaborate effectively

Effective communication within the design team and between the client and architect is vital for the success of building for the arts. One of the most critical aspects of improving the process of theatre design is to not only incorporate theatre professionals, but to also adopt their less adversarial approach to designing and collaborating. Replicating this camaraderie with ambition and drive will certainly benefit the efficiency of building projects and result in better building outcomes. This could be made feasible by involving consultants earlier in the design process than is suggested in the RIBA Plan of Work, allowing each member of the design team to have the same opportunity to contribute to the design, work with the client and collaborate effectively

From interviews, theatre makers are passionate about being involved in theatre architecture with their priorities largely focussing on the functionality of the space. Involving theatre professionals would not result in major design changes, but small functional input, particularly during value engineering, could help to mitigate the frustrations of the users of the space.

Schematic plan of The SPACE

Effective communication within the design team and between the client and architect is vital for the success of building for the arts. One of the most critical aspects of improving the process of theatre design is to not only incorporate theatre professionals, but to also adopt their less adversarial approach to designing and collaborating. Replicating this camaraderie with ambition and drive will certainly benefit the efficiency of building projects and result in better building outcomes. This could be made feasible by involving consultants earlier in the design process than is suggested in the RIBA Plan of Work, allowing each member of the design team to have the same opportunity to contribute to the design, work with the client and collaborate effectively.

The SPACE North Street Elevation | Marsh Grochowski Architects

Although this dissertation focused on theatre buildings, the lessons learnt from this building type could be applied to other specialist buildings. It should be common practice for professionals using a new building to be involved in the design process. This will have to be explored in further research but could help to improve the functionality in many bespoke building types.